Here you can choose to read more about various topics: Click on the small +

Understanding Anxiety : A Psychological Perspective

Understanding Anxiety : A Psychological Perspective

Understanding Anxiety : A Psychological Perspective

Fear is a fundamental emotional response to perceived threats, essential for survival. In contrast, anxiety represents a learned fear response that has become ingrained and automated within the brain’s neural pathways.

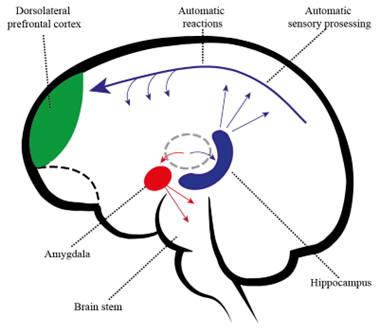

Sensory inputs from our environment are relayed to the brain, where they are initially processed by the amygdala, which serves as the brain’s alarm system. This structure evaluates whether stimuli are threatening and, if so, activates the brainstem to initiate the fight, flight, or freeze responses. This evolutionary adaptation has been crucial for human survival, enabling quick reactions to life-threatening situations.

However, the brain’s capacity to remember these fear responses can lead to the development of an automated fear response after repeated exposures. This process is akin to other learned behaviors, such as riding a bicycle, where repeated practice leads to automaticity.

Anxiety occurs when this automated fear response is triggered inappropriately, in the absence of actual danger. It involves the persistent storage of a learned fear response to stimuli that are typically non-threatening, reflecting a misfiring of the brain’s threat-assessment system. Understanding and addressing anxiety thus requires a reevaluation of these learned responses, aiming to recalibrate the brain’s perception of danger and response mechanisms.

Why Does Anxiety Arise? Understanding the Mechanism

Sensory impulses and fear responses are transmitted to the cerebral cortex, where automatic processing of sensory information occurs. If these reactions are repeated, a “pathway” is formed in the brain, leading to an automatic response when a similar situation arises again. This results in an unconscious fear response, where the individual may not be aware of what they are actually afraid of.

When facing genuinely dangerous situations, this automatic brain response is highly advantageous. However, the brain also has the tendency to mislabel harmless stimuli as threats, such as exams or spiders. With conscious awareness and mindfulness, we can prevent these harmless stimuli from being stored as threats.

Less than 1% of all sensory impulses reach our conscious awareness or cognitive processes, located in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. If we manage to assess the situation at this stage—for example, realizing “that tiny spider is not a threat”—we can prevent it from being encoded as an automatic fear response.

This description simplifies the complex process of how anxiety develops, but understanding it is crucial. By continuously monitoring our own fear responses and correcting them when they misfire in response to non-threatening stimuli, we can prevent the accumulation of new anxieties.

How is Anxiety Treated?

Cognitive therapy and medication are the most common treatment modalities for anxiety. However, recent research highlights the groundbreaking effects of attention training.

A research project at Florida International University demonstrated that brief attention training alleviated anxiety in 50% of cases where cognitive therapy and medication had been ineffective. The efficacy increased to 58% after two months.

On this website, you can access attention training exercises for free. These exercises are structured similarly to the training used by researchers at Florida International University, providing an effective resource for managing symptoms of anxiety.

Support for Exam Anxiety

Attention training, which is available for free on this site, is the best and most sustainable solution for managing exam anxiety.

However, if you have not practiced and find yourself in an acute situation, you can use the following tip:

During an exam, if you find your attention drawn to your body, you might hear your heart pounding and feel your hands sweating. Is this helpful? No. Instead, shift your focus to a simple mental exercise. Start with 100 and subtract 3, continue subtracting 3 repeatedly. If you’re adept at mental math and find this too easy, try subtracting 4.7, then another 4.7, and so on. This will deplete your ‘attention account,’ leaving no room for thoughts about sweaty hands or a racing heart—effectively dissipating your nervousness.

What is Depression?

Depression can be understood as an automatic reaction that, at some point, we have learned. This phenomenon is often described as learned helplessness.

Depression is typically characterized as a mental illness marked by persistent low mood. Thoughts such as “I can’t do this,” “I don’t want to,” “I’m afraid to,” along with a negative self-perception, are prevalent when one is experiencing depression. Individuals with depression have learned a pattern of focusing on the negative aspects of each situation.

Consider the metaphor of a half-filled glass of water: Do you see it as half-full or half-empty? Are you grateful for the water you have, or are you sad that you don’t have a full glass? Where you direct your attention can significantly impact your emotional state. Focusing on aspects that make you sad will likely increase feelings of sadness, whereas directing attention toward positive aspects can foster happiness.

How Does Depression Develop?

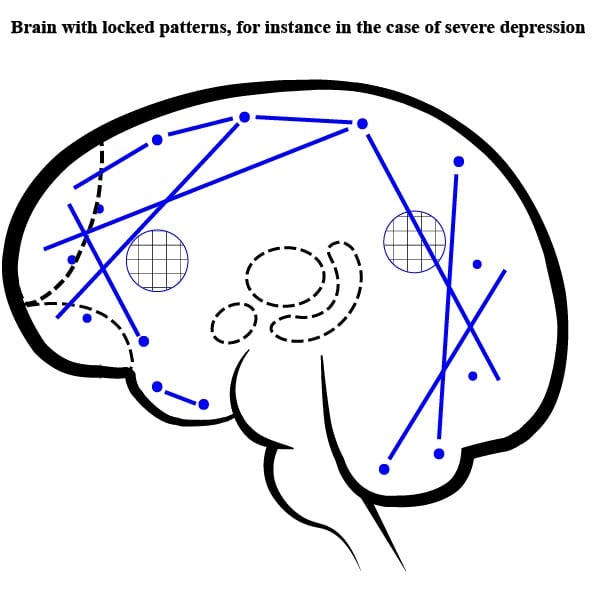

Each time you choose, whether consciously or unconsciously, to focus on the negative aspects of a situation, a neural pathway is created in the brain. Repeated focus on the negative can solidify this pathway into a persistent pattern.

Brain scans can reveal these pathways or patterns. While individual tracks may not be visible, we can observe specific groupings or regions in the brain that activate simultaneously. It is also evident that there are other areas of the brain that do not communicate at all. This lack of connectivity in certain brain regions contributes to the sustained nature of depressive states.

Treatment Approaches for Depression

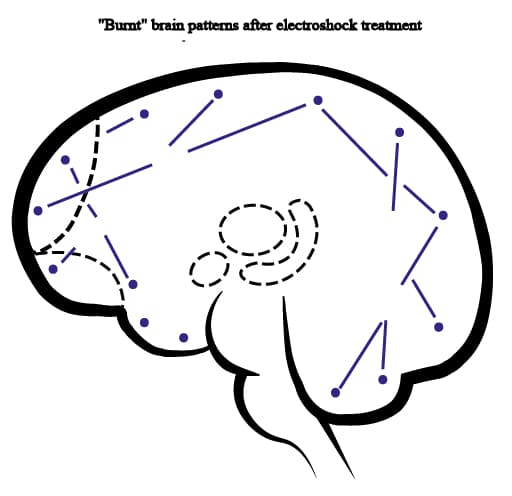

Medical science addresses depression through several approaches, including cognitive therapy, medication, and, in severe cases, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). ECT is particularly useful for individuals who are profoundly entrenched in their depressive states, as it “resets” some of the rigid patterns in the brain. However, the passage of electrical currents through the brain does not selectively target only the maladaptive patterns, leading to side effects such as memory issues or gaps in memory recall.

Recent research, however, points to the transformative impact of attention training. Studies conducted at the University of Oxford have explored this method extensively. Their findings suggest that just two weeks of attention training can act as a cognitive ‘vaccine’ against depression, effectively bolstering psychological resilience.

On this website, you can access these attention training exercises for free. They are designed in the same way as those used by researchers at the University of Oxford, providing an accessible tool to help guard against depression.

What is Stress?

In psychological literature, stress is defined as a condition arising from environmental circumstances that are perceived as burdensome by an individual, or that exceed their resources and threaten their well-being. It is not the situation itself that causes stress, but rather how the situation is perceived and evaluated.

Stress is not a disease but a physiological response to perceived challenges or burdens. It can also be seen as a signal from the body, indicating a need for personal action.

For example, encountering a tiger in the savannah triggers a stress response. In such a scenario, it is ineffective to merely wish the tiger would not attack or to hope someone else will intervene—such actions could result in being eaten. Instead, one must take direct action—whether fighting, fleeing, or staying still in hopes of remaining unnoticed.

Similarly, when experiencing stress in everyday life, it is imperative to take proactive steps to manage the situation.

Why Do People Experience Stress?

Consider two individuals working in the same environment, subjected to identical pressures. Why might one become debilitated by stress and take sick leave, while the other remains unaffected? It is common to blame external circumstances for stress, but since both individuals face the same conditions, the root cause cannot solely be the external stressors. Instead, it lies in how each individual copes with or manages the situation.

Each person has developed automatic ways of responding to stress, which means one might not experience stress while the other does. This phenomenon can be understood as learned helplessness in the context of stress.

Research into their coping strategies reveals a crucial difference between those who experience stress and those who do not. Individuals who manage stress effectively tend to focus on what they can control, whereas those who succumb to stress focus on what is beyond their control. This difference in focus is pivotal in determining their susceptibility to stress.

How to Avoid Stress?

When a situation is perceived as burdensome, the amygdala, an ancient part of the brain shared with other animals and reptiles, becomes activated. The primary function of the amygdala is to ensure survival in the face of perceived threats—a function that has aided our survival throughout evolution. We owe much to the amygdala for this.

However, there is a complication. The amygdala was ‘programmed’ millions of years ago, during a time when saber-toothed tigers and other predators saw humans as prey. This outdated programming causes the brain to react to modern non-life-threatening stressors—such as an overload of work tasks—as if they were deadly threats, triggering automatic fight, flight, or freeze responses.

The process begins with perception. If one focuses on the overwhelming amount of unfinished tasks, the amygdala is activated, leading to stress. Conversely, if one can control their focus and direct attention to the tasks they are completing, they can avoid triggering the amygdala.

Gaining control over where to direct attention requires practice, but just a few minutes of training over several weeks can have profound effects. You can access training exercises for free on this website. This training helps in managing how one perceives and reacts to potential stressors, ultimately reducing the likelihood of a stress response.

How to Prevent Stress?

If one has not yet mastered the skill of attention control, there are other untrained measures that can be taken to mitigate daily stress. A key strategy is maintaining balance in all aspects of life. Imbalance triggers the amygdala because it is perceived as a threat to survival.

Consider this example: Suppose you earn £2,300 per month after taxes, but your expenses amount to £2,800. This discrepancy creates an imbalance. Many believe that an additional £500 per month would solve the issue. However, the real problem is not the deficit itself but the imbalance between income and expenses. Even if your salary were to double, the issue might be resolved temporarily, but soon enough, the problem would resurface. No matter how much money you receive, a shortage will persist as long as there is an imbalance. To establish balance, the first step is to reduce expenses. Only after achieving balance will a salary increase truly be beneficial.

In the context of employment, many people today experience stress at work due to a perceived imbalance between the volume of tasks and the time available to complete them. Would reducing some tasks or doubling the workforce solve this issue? Perhaps for a month or two, but the problem would likely recur.

Ensuring balance in all aspects of life is an effective way to prevent stress. This approach helps in reducing the activation of the amygdala by maintaining a perceived sense of security and control over one’s environment.

Workplace Stress. Responsibility and Solutions

Both employers and employees play crucial roles in fostering a healthy work environment. This shared responsibility is essential for creating a supportive workplace and minimizing stress.

There is often a tendency to place all responsibility on employers, especially citing excessive workloads. Furthermore, if conflicts or harassment among employees lead to stress, the burden again shifts to the employer to take corrective action, as directly advised by the Labour Inspectorate. However, there is insufficient focus on the individual actions that employees can take to manage stress and improve well-being at work.

The argument that large work volumes and pressure cause work-related stress is common, yet international comparisons reveal fewer instances of stress and psychological disorders in countries with high work pressures.

The World Health Organization (WHO) conducted a comprehensive study demonstrating that symptoms of stress are not merely a result of “overwork” but rather stem from prolonged ruminations and worries about the genuine challenges we face in life. When such concerns dominate hours of our daily thoughts, it is natural for symptoms like stress and burnout to emerge.

Harvard Medical School conducted extensive research across 160 major workplaces, finding that long-term interventions aimed at reducing stress and improving mental health are ineffective. These findings suggest that employers might not have direct control over reducing workplace stress, highlighting the importance of exploring what individual employees can do instead.

Numerous studies have shown the remarkable effectiveness of attention training in combating stress. For instance, research at Uppsala University found that just 12 minutes of attention training per day over four weeks not only had a significant impact in the short term but also provided lasting effects.

On this website, you can access mindfulness training for free, designed in the same effective manner identified in various studies. This training represents a practical step that employees can take to fulfill their shared responsibility in preventing stress. It is the employer’s responsibility to provide access to such training opportunities.

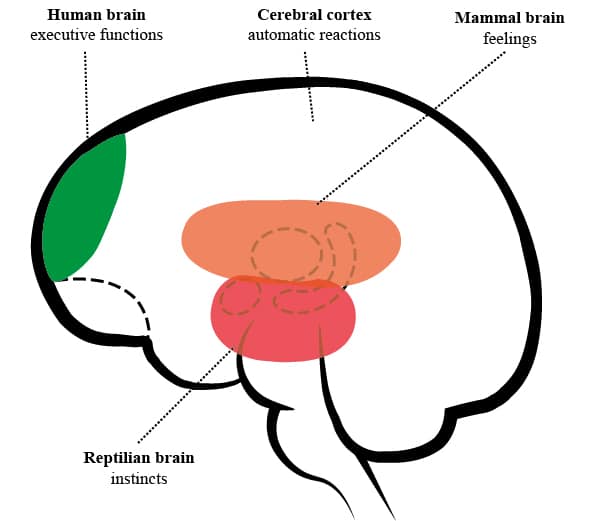

The Triune Brain Model and the Evolution of the Brain

American neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean proposed the triune brain model to describe the structure and functions of the brain as comprising three distinct layers, each evolved at different stages and serving unique functions.

These layers are sequentially overlaid through evolutionary processes: the reptilian brain, the limbic system, and the neocortex. Respectively, they are known as the reptilian brain, responsible for instinctual survival behaviors; the limbic system, or mammalian brain, which governs emotions and memory; and the neocortex, or human brain, which enables higher cognitive functions such as reasoning, planning, and language. This model highlights the complexity of brain evolution, illustrating how newer, more sophisticated structures have built upon the older, more primitive ones to give rise to the diverse capabilities of the human brain and mind.

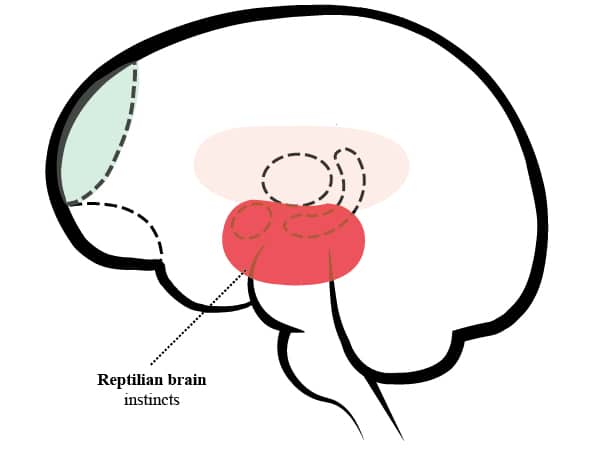

The Reptilian Brain and the Brainstem

Approximately 500-650 million years ago, the brain was predominantly composed of the brainstem. Positioned at the end of the spinal cord, the brainstem encompasses all vital, involuntary control centers, including those responsible for regulating heart function, blood circulation, and respiration.

In English, it is often said that the brainstem is the home of the ‘four F’s’: Fight, Flee, Freeze, and Fuck. These responses—fighting, fleeing, freezing, and fucking—were essential for survival, territorial dominance, finding a mate, and ensuring species continuation, similar to behaviors observed in reptiles and fish. Consequently, this part of the brain is referred to as the reptilian brain, highlighting its primary role in basic survival mechanisms.

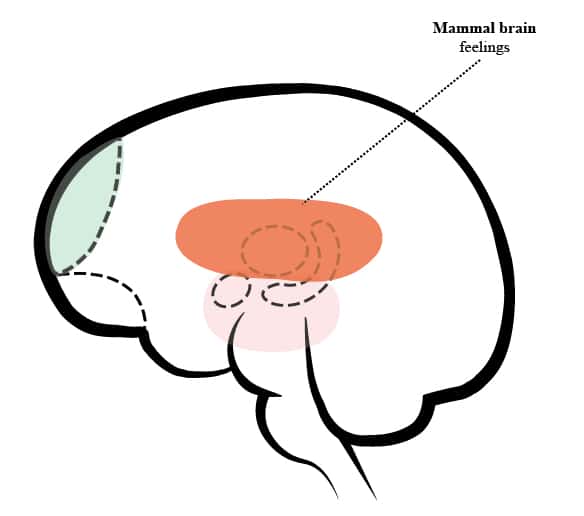

The Mammalian Brain

Approximately 23 million years ago, the “paleomammalian complex,” also known as the limbic system or mammalian brain, emerged. This complex did not develop overnight but evolved gradually, representing a significant advancement over the reptilian brain.

The limbic system, centered around the amygdala and hippocampus, is nestled between the cerebral cortex and the brainstem, bridging consciousness with primal drives and instincts.

The primary function of the limbic system is to differentiate between what feels pleasurable and rewarding, and what feels adverse and should be avoided. Thus, the limbic system is essentially the seat of emotions. It reinforces behaviors designed to maximize survival and steers the organism away from potentially threatening or uncomfortable situations. This system plays a crucial role in emotional processing and memory, influencing both the formation of personal and social bonds and our survival strategies.

The Human Brain

Over the last 2.5 million years, there has been a significant evolution of the neocortex, coinciding with the development of higher vertebrates and humans. This part of the brain was traditionally referred to as the “human brain.”

Throughout most of this period, the neocortex expanded in size, although this trend has plateaued in the last 200,000 years. The majority of the neocortex houses all that we have learned throughout life, consisting of learned patterns in the form of unconscious automated stimulus-response routines. For example, when we teach a dog to sit at the command “sit,” it involves an unconscious learned pattern. Similarly, riding a bicycle also becomes an unconscious learned pattern. In this aspect, there is no difference between humans and animals.

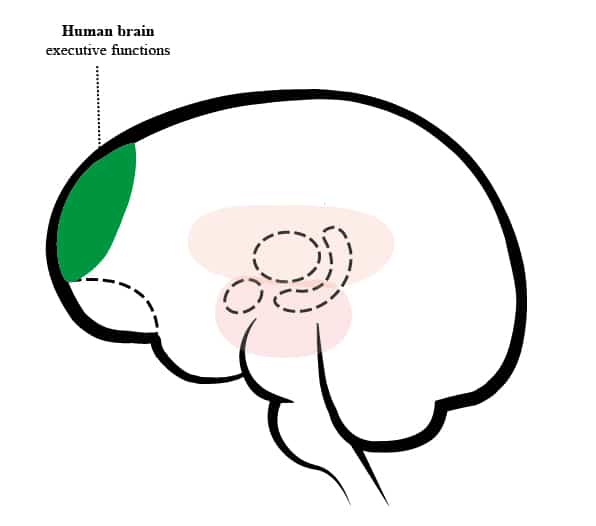

However, around 200,000 years ago, changes in our chromosomes led to significant developments in the prefrontal part of the neocortex, particularly in the area known as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which is now identified as the “human brain.” This region is far more advanced than other parts and shows high activity levels when we engage our executive functions.

Executive functions are cognitive processes that distinguish us from animals. These include higher cognitive abilities such as rational judgment, imagination, time management, planning and prioritization, problem-solving, attention control, self-reflection, inhibitory control over other brain regions, and the reprogramming of previously learned habits and response patterns.

Additionally, this area serves as the control center for our consciousness, self-awareness, and language use. These functions are unique to humans and are not found in other animals, hence the term “human brain.” We train these functions throughout our upbringing, and although many adults may have deficiencies in one or more areas, these capabilities can be trained and improved throughout life.

The Function of the Neocortex

When a child is born, their brain is akin to a “blank slate,” with the exception of the reptilian brain, which is operational from birth. As the child grows, the limbic system and subsequently the neocortex become activated. The neocortex serves as the brain’s storage unit where all learned information is kept and converted into automatic reactions.

For instance, learning to ride a bicycle initially requires significant focus to maintain balance, watch the road, and pedal. However, over time, neural networks are established in the neocortex that automate these responses, allowing you to multitask, such as talking on the phone while biking, without issue.

The neocortex not only stores intentionally learned information but also unintentional learnings. For example, if you had a family member who consistently managed to get their way by acting offended, your neocortex stores this behavior as well. If this behavior is observed repeatedly, it becomes an automatic response pattern that you might unconsciously replicate to achieve similar outcomes.

Thus, the neocortex contains both adaptive and maladaptive automatic response patterns. With proper brain training, it is possible to modify these maladaptive patterns, enhancing one’s ability to respond more appropriately in various situations.

Brain Plasticity

Brain Plasticity

Brain PlasticityNeurons that are not used will eventually die and cannot be regenerated. However, throughout our lives, we have the ability to form new connections between the neurons we retain, enabling us to learn new things—both beneficial and detrimental.

Consider this hypothetical scenario: You know how to ride a bike but want to learn “how not to ride a bike.” While this sounds absurd, it illustrates that we are continually learning, sometimes even in nonsensical ways.

If you intentionally fall every time you get on a bike over a period, you will forge new neural connections that create an automatic response pattern of falling when you mount a bike. This example highlights how you can leverage the concept of brain plasticity to alter automatic response patterns that you find maladaptive. By consciously practicing new behaviors, you can reshape your brain’s wiring, demonstrating the flexibility and adaptability of neural pathways.

Mental Training and Attention Training

The goal of mental training is to optimize your brain’s capacity and enhance your ability to perform tasks. Attention training, on the other hand, aims to refine your brain’s processes to better support your true self.

Mental Training

An illustrative study was conducted with basketball players from Arizona. The players were divided into two groups: one group physically practiced shooting three-point baskets, while the other engaged in mental training, imagining hitting three-point shots without physically practicing. After several weeks, the results showed that the players who used mental imagery were more successful at making three-point shots than those who physically practiced. This was because the mental training group had internalized only successful shots, whereas the physical group also remembered their misses. Mental training enabled them to perform better by focusing solely on successful outcomes.

Attention Training

Consider the control of attention with this example: Imagine an elephant walking on a green meadow—this is simple for most people. Now, imagine you are driving a red sports car with a tiger sitting next to you, licking its lips. In a quick response, you bite into a sliced lemon, knowing tigers dislike the taste, ensuring the tiger won’t harm you. At this point, the elephant from your earlier visualization is likely forgotten as your attention has shifted. In this scenario, I directed your attention, but you can also do this yourself. If the elephant brought on unpleasant feelings, you could redirect your focus to a positive scenario (the tiger in the car) to dispel the negative emotions.

The better you are at controlling your attention, the better you can manage all other executive functions. You can train your attention on this website to improve your overall ability to ‘be’.

Automatic Unconscious Reactions

Automatic Unconscious Reactions

Your brain is inherently lazy, structured to convert as much as possible into automatic, unconscious reactions. Do you find yourself sitting in the same chair each time you eat? Or performing the same routine each morning? Your brain is trying to coax you into a half-asleep, zombie-like state.

To actively train your brain in everyday life, you need to introduce variations in your routine. Consider sleeping with your head at the foot of the bed or switching to the other side of the bed. Set your alarm to ring either half an hour earlier or later than usual. If you’re used to having your mobile phone glued to you throughout the day, try putting it aside for a few hours. Alternatively, take a winter swim in the ocean if you’re typically a summer swimmer only. These simple changes can stimulate and train your brain during an ordinary day, helping to enhance cognitive flexibility and prevent the stagnation of neural activity.